We are looking for 107 people to join a special group of monthly donors called Partners for Peace. Will you be one? As a partner, you provide the steady support needed for emergency response and long-term work for change. Start your monthly gift before September 30 to help us plan for the year ahead!

Quaker action for a just world

A: Solitary confinement of prisoners goes by a number of names—isolation, SHU (special housing units), administrative segregation, supermax prisons, the hole, MCU (management control units), CMU (communications management units), STGMU (security threat group management units), voluntary or involuntary protective custody, special needs units, or permanent lockdown.

Although solitary confinement conditions vary from state to state and among correctional facilities, systematic policies and conditions include:

Beginning in the early 1970s, prison and jail administrators at the federal, state, and local level have relied increasingly on isolation and segregation to control men, women, and youth in their custody. In 1985, there were a handful of control units across the county. Today, more than 40 states have super-maximum security—or “supermax”—facilities primarily designed to hold people in long-term isolation.

A: There are more than 80,000 men, women, and children in solitary confinement in prisons across the United States, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Note that figure is a decade old and doesn’t include people in jails, juvenile facilities, and immigrant detention centers. Nearly every state uses some form of solitary confinement, but there’s no federal reporting system that tracks how many people are isolated at any given time.

Prisoners are often confined for months or even years, with some spending more than 25 years in segregated prison settings. As with the overall prison population, people of color are disproportionately represented in isolation units.

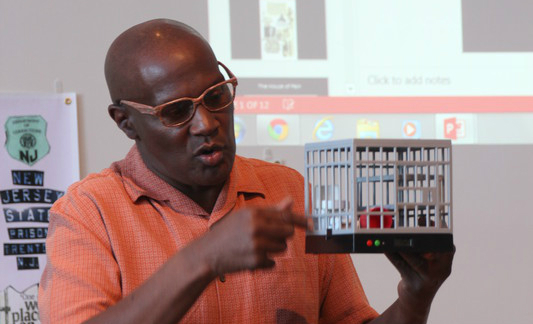

AFSC's Ojore Lutalo spent 22 years in solitary confinement. AFSC

A: Prisoners can be placed in isolation for many reasons, from serious infractions, such as fighting with another inmate, to minor ones, like talking back to a guard or getting caught with a pack of cigarettes.

Other times, prisoners are thrown into solitary confinement for not breaking any rules at all. Prisons have used solitary confinement as a tool to manage gangs, isolating people for simply talking to a suspected gang member. Prisons have also used solitary confinement as retribution for political activism.

These effects are magnified for two particularly vulnerable populations: juveniles, whose brains are still developing, and people with mental health issues, who are estimated to make up one-third of all prisoners in isolation.

A: Yes. Prison isolation fits the definition of torture as stated in several international human rights treaties, and thus constitutes a violation of human rights law. The U.N. Convention Against Torture defines torture as any state-sanctioned act “by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person” for information, punishment, intimidation, or for a reason based on discrimination.

Since the 1990s, the U.N. Committee Against Torture has repeatedly condemned the use of solitary confinement in the U.S. In 2011, the U.N. special rapporteur on torture warned that solitary confinement “can amount to torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment when used as a punishment, during pre-trial detention, indefinitely or for a prolonged period, for persons with mental disabilities, or juveniles.”

If a person isn’t mentally ill when entering an isolation unit, by the time they are released, their mental health has been severely compromised. Many prisoners are released directly to the streets after spending years in isolation. Because of this, long-term solitary confinement goes beyond a problem of prison conditions, to pose a formidable public safety and community health problem.

AFSC's Bonnie Kerness (center) and Ojore Lutalo (second from left) have worked for decades to end solitary confinement. AFSC

A: Prisoners and their families have taken the lead in making the public and policymakers aware of this cruelty taking place in U.S. correctional facilities, forming coalitions and working to ensure their stories are told in the news media. Several faith-based organizations, including AFSC, have accompanied survivors of solitary confinement in calling for an end to the practice.

In recent years, several states have reexamined the use of solitary confinement in state prisons, but we are far from abolishing this shameful practice in the U.S.

Prison isolation must end—for the safety of our communities, to respect our responsibility to follow international human rights law, to take a stand against torture wherever it occurs, and for the sake of our common humanity.